For many stakeholders at the 7th Pan-African Conference (PAC) on Illicit Financial Flows (IFFS) in Nairobi, Kenya, the debate was not on whether the continent should tax digital transactions but how to tax in most of the economies that are steadily becoming digitalized. By Olusegun Oruame.

The digital economy has high prospect to leapfrog many African countries but there is also high possibility of igniting a new form of slavery, some experts at the recent 7th Pan-African Conference (PAC) on Illicit Financial Flows (IFFS) in Nairobi, Kenya have warned.

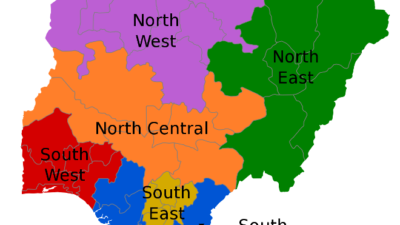

While many of the major economies on the continent including Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa seek to explore new opportunities in the digital economy and reduce their overwhelming dependence on export of natural resources or even tourism, the consensual thinking is that there is a need to be both cautious and strategic in adopting policies on data rights, protection, and storage; and taxing digital goods and services that will not leave the continent empty of dividends.

Since the early 90s, many African countries have embraced liberalization and deregulation as key economic policies to open once closed sectors to competition and expand local markets. The increasing digitization of their economies have also exposed the underbelly of deregulation as well as open up new challenges on whether and how to tax digital transactions that cover services and goods in-country or across borders.

While the likes of Facebook, Twitter, Amazon and Alibaba are increasingly dominating the new ecommerce sector for delivery of services and goods, African governments are debating whether and how to tax these new economic engagements. They are also beginning to contend with the arguments over what constitutes the limit or extent of data sovereignty. Most tax regimes in Africa do not cover digital trades and there is global pressure by the big tech companies on developing economies not to tax digital transactions so as not to stifle growth of global ecommerce or even trade liberalization.

“Liberalization of digital trade will actually weaken the ability of developing countries to generate resources for, as well as undertake, digital industrialization and the investment in public services necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs],” said Deborah James in her presentation on Implications of Tax-Related Provisions in Digital Trade at the PAC event in Nairobi.

James, a cross-border taxation expert and researcher at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, is convinced that the aspiration by big tech companies in the developed economies to make digital services and goods tax exempt would only undermine ability of developing economies to benefit from digital economic activities that define their own unindustrialized space.

Her argument is that developing economies need to tax digital trade to have the needed fund to invest in digital industrialization. The big tech giants must be willing to part with a percentage of their earnings in developing economies so that those growing economies could further strengthen the local backbone infrastructures and support their own budding tech startups.

Naro Omo-Osagie, Abuja based lawyer and expert on tech and policy; Edward Kusewa, lecturer at Saint Paul’s University, Nairobi and Pirfa Jingfa Tyem, a tax expert formerly with the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) of Nigeria and now currently a legislator at the Plateau State House of Assembly agreed that of necessity, developing economies must both implement digital taxations and also evolve proper policy frameworks able to boost their revenue base from sustainable digital economic models.

“Since digital trade is currently dominated by developed countries, raising revenues through both taxing digital transactions and taxing digital corporate profits – while protecting the policy space for infant digital industries and ownership of data – are much more likely to result in raising revenue that can be used for digital industrialization, public services, and achieving the SDGs,” said James.

Elsewhere in her book on ‘Anti-development Impacts of Tax-Related Provisions in Proposed Rules on Digital Trade in the WTO’, James argued that the ability of developing countries to achieve the SDGs will depend in large part on their ability to mobilize resources including through taxation. But new proposed rules in the WTO are threatening all countries’ ability to generate fiscal revenues through taxing the activity of transnational corporations. Under the guise of new talks on ‘e-commerce’, the largest TNCs [transnational companies] are seeking to rig international rules to prevent governments from being able to assess tariffs on international transactions, as well as to assess taxes on corporate profits. If the talks in the WTO result in a binding agreement, the fastest-growing and most profitable sectors of the economy will be permanently released from the responsibility of contributing to the social and physical infrastructure on which their businesses are based, and governments will be unable to meet the social and development needs of their populations.

She had also drawn attention to this threat in her article with the title: The biggest threats to the stability of the world economy — and Google is one.

She states: “In the early 1990s, transnational corporations (TNCs) in the agriculture, services, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing sectors each got agreements as part of the WTO to lock in rights for those companies to participate in markets under favorable conditions, while limiting the ability of governments to regulate and shape their economies. The topics corresponded to the corporate agenda at the time.

“Today, the biggest corporations are also seeking to lock in rights and handcuff public interest regulation through trade agreements, including the WTO. But today, the five biggest corporations are all from one sector: technology; and are all from one country: the United States. Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft, with support from other companies and the governments of Japan, Canada, and the EU, are seeking to rewrite the rules of the digital economy of the future by obtaining within the WTO a mandate to negotiate binding rules under the guise of “e-commerce.”

“However, the rules they are seeking go far beyond what most of us think of as “e-commerce.” Their top agenda is to ensure free ― for them ― access to the world’s most valuable resource ― the new oil, which is data. They want to be able to capture the billions of data points that we as digitally-connected humans produce on a daily basis, transfer the data wherever they want, and store them on servers in the United States. This would endanger privacy and data protections around the world, given the lack of legal protections on data in the US.

At the 7th PAC in Nairobi, she warned that “’big tech’ companies don’t like paying tax. Citing the Washington Post, she claimed Amazon paid no federal taxes on $11.2 billion in profits for 2018.

She argued that the agenda of the big tech’ companies in digital trade as expressed at the WTO is to lock in their business model into international law and achieve their major goals which include:

- Unfettered rights to access markets

- Unbroken deregulation (change in government should not mean possibility of altering the policy or rules on deregulation or market liberalization)

- Unfettered access to cheap labour stripped of its rights

- Tax avoidance and evasion; and

- Control of big data and technology

Africa’s major concern should be how best to leverage the digital economy by having both the right policy and infrastructures in place. Without these, it stands little chance of being able to negotiate itself into being s strong stakeholder in the global ecommerce, said Kusewa to IT Edge News in Nairobi.

For James, developing economies must put up a strong resistance to the agenda by Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, and the other big tech companies to dominate data ownership and exert a no-tax policy on services and goods delivered by them into developing economies.

This article was first published in IT Edge News.