Tear down these walls

Africa’s internal trade deals look good on paper. A pity that they are rarely followed

Two of the largest regional trade accords in history were agreed on last year. The Trans-Pacific Partnership involves 12 countries in Asia and the Americas, and was the subject of headlines and heated debate. But most people have never heard of the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), which covers 26 African countries. It will create the biggest free-trade area on the continent, “from Cairo to the Cape”, as its supporters boast.

Many in the developing world see global trade as rigged in favour of rich countries. But African regional integration is all the rage. The continent features 17 trade blocs. The TFTA aims to join up three of them: the East African Community (EAC), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). At a conference on African business on February 20th-21st in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh, several leaders called for a united African market.

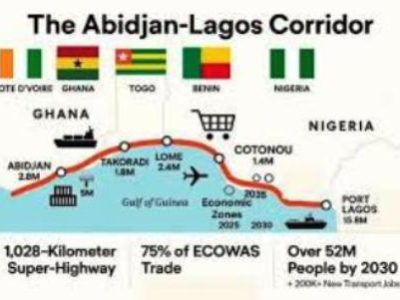

An abundance of borders has long divided the continent’s 54 countries, limiting economies of scale. Fixing common problems such as a shortage of roads takes teamwork—and in turn should lead to more integration. Average transport costs in Africa are twice the world average and are thought to harm trade on the continent more than tariffs and other barriers.

A shame, then, that regional economic deals are often poorly implemented. An African firm selling goods on the continent still faces an average tariff rate of 8.7%, compared with 2.5% overseas, says the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). That is one reason why intra-African trade as a percentage of total African trade is well below what is seen in other poor regions (see chart).

Nearly all African countries are party to more than one regional agreement. These overlapping allegiances can tie them in knots. Members of COMESA, for example, impose a common external tariff on goods of non-members. But several members are also in the SADC free-trade area, which requires lower tariffs on goods from some non-COMESA states. The TFTA is meant to iron out these differences, but the details are still to be decided.

African countries vary in size, geography and resources, so trade deals affect each differently. Manufacturing tends to cluster in powerhouses such as Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. Small agricultural producers fear being swamped with food from larger neighbours. There are no mechanisms for helping the losers. So it is difficult to convince countries to make sacrifices in order to increase trade.

Whether to protect their dominance or avoid hardship, most countries revert to protectionism. Take the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). It is meant to be a customs union, but has an extensive list of exceptions. Two decades after it promised free movement of people, goods and transport, implementation is poor. East Africa does better, but KarimSadek, the director of Rift Valley Railways in Kenya and Uganda, says that not having to stop at the border would make his life easier. “You get used to the inefficiencies.”

Non-tariff barriers are not only an African problem. Product standards and rules of origin are used by America to block Mexican goods under NAFTA. But evidence cited by UNCTAD suggests that the reduction of tariffs in Africa has led to an increase in the use of other obstacles. In SADC such protectionism has resulted in more imports from non-SADC countries. Clothes, for example, are required to be both manufactured and sourced in SADC countries to qualify for preferences. Since few textiles are produced in the region, the rules have stifled trade in garments.

Bureaucracy is expensive to overcome. According to research by Nick Charalambides of Imani Development, a consultancy, Shoprite, a South African retailer, spent $5.8m dealing with red tape in 2009 in order to gain $13.6m in duty savings under SADC. Others avoid the hassle of customs: informal trade is thought to provide income to over 40% of Africa’s population.

Some think Africa needs to approach trade differently. “The first question that should be asked is: what can we trade with each other?” says BineswareeBolaky of UNCTAD. Often the answer is: not much. Most African countries produce a narrow range of goods and have export sectors geared towards supplying rich countries. Few have significant manufacturing bases and, unlike in developing Asian countries, there is little trade in inputs or services that might lead to African chains of production.

The volume of intra-African trade is so small that fixing these problems, and upgrading the continent’s infrastructure, may not seem worth the expense to some countries. So UNCTAD recommends creating an integration fund, financed by relatively rich African states, to pave new roads and build export capacity in poorer countries. The African Development Bank handed out over $1 billion in the past two years with the explicit aim of boosting intra-African trade. But that risks becoming an objective in and of itself. “You still need to be flogging stuff to big countries,” says Alan Winters of the University of Sussex.

In their zeal to integrate, African leaders may also be using the wrong model. Broad and shallow agreements are the norm, but the continent’s most successful economic bloc consists of just five countries. EAC members keep good data, and a public scorecard holds them accountable for non-tariff barriers. “There you have a small group of countries that is taking it seriously and making some progress,” says Jaime de Melo of the University of Geneva. Talk of a common currency in East Africa and even a political federation do not seem far-fetched. It is a stretch to think that the TFTA will lead to anything similar.

Courtesy: http://www.economist.com/news/21693562-africas-internal-trade-deals-look-good-paper-pity-they-are-rarely