By Dr. A. J. Anuga and Odaudu Ijimbli

The recent commissioning of the Dangote Refinery, and its subsequent importation of US light crude, sent ripples through global economic commentary. Here, ostensibly, was a symbolic rupture: a “Third World” nation, long shackled as a raw materials appendage to Western industrial complexes, was now importing a strategic commodity from Texas to refine and re-export.

This inverted the classical dependency paradigm, presenting Nigeria not as a pit-stop for extraction, but as a potential nexus of value-addition. Yet, this promising anomaly is perilously close to becoming a historical footnote a glittering monument to private ambition, overshadowed by the state’s profound and shortsighted neglect of the very engine that could sustain such innovation: its universities and scientific ecosystem.

Dangote Refinery is a child of accident, not design

At its core, the Dangote Refinery is a child of accident, not design. It emerged not from a coherent, state-driven industrial policy, but from the confluence of a billionaire’s capital, chronic domestic fuel scarcity, and the eventual withdrawal of costly petrol subsidies. It is a private solution to a public failure.

While celebrated, it risks being a solitary cathedral in a desert of industrial stagnation because Nigeria has failed to cultivate the intellectual soil necessary for replication and evolution. The state’s handling of its university system epitomized by its perennial, adversarial conflicts with academic unions like the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) reveals a catastrophic failure of political imagination.

The Folly: Sacrificing the Future on the Altar of Immediate Political Economy

The Nigerian state’s approach to its universities is rooted in a rentier political economy. The state, historically configured as a distributor of oil rents rather than a cultivator of productive capital, views public expenditure on education not as an investment, but as a burdensome cost to be minimized. When ASUU advocates for improved funding, infrastructure, and lecturer welfare, it is advocating for the conversion of national wealth from mere consumption into human and knowledge capital. The government’s response protracted strikes, broken agreements, and rhetorical dismissal of these demands as unsustainable is a stark declaration of its priorities.

This is the height of shortsightedness. The Dangote complex does not operate in a vacuum. It requires chemical engineers, metallurgists, process analysts, logistics experts, and environmental scientists. Its long-term viability depends on research into catalyst optimization, petrochemical by-products, and alternative energy transitions.

Where are these experts to be trained? Where is this research to be conducted? In dilapidated laboratories, under demoralized lecturers, within universities running on generators, with libraries devoid of current journals? By systematically devaluing academia, the state ensures that the Dangote Refinery must import not just crude. But it must also import the sophisticated human expertise to run it, perpetuating a new form of dependency.

The Risk: A Flash in the Pan, Not a Forging Fire

Without a parallel revolution in knowledge production, the Dangote phenomenon will remain an isolated, import-dependent enclave. It will refine foreign crude with foreign technology, maintained by foreign technicians. It will generate profits, but not a generative industrial culture. The “innovation” will be confined to the business model of a single conglomerate, not diffused into a national capacity for complex manufacturing.

This is the peril: Nigeria risks creating a “refinery enclave” reminiscent of the “oil enclave”, a high-value island disconnected from the productive mainland of its own economy. The value chain will remain truncated. The dream of becoming Africa’s producer/manufacturer will die at the university gates, where the next generation of inventors, researchers, and critical thinkers are being starved of tools and hope.

The Path Forward: Leveraging the Precedent for a Paradigm Shift

The Dangote Refinery presents a tangible, powerful precedent. It proves that large-scale, complex industrial projects are possible on Nigerian soil. The task now is to use this as a catalyst for a deliberate socio-economic paradigm shift. This requires a fundamental reorientation of the state’s role from rentier to developer.

- The University as Industrial Forge: The government must end the warfare with ASUU and embrace a grand bargain. Increased funding must be tied to curricular and research reform. Engineering and science faculties should be directly linked to industrial clusters. The Dangote Group and similar entities could be incentivized to fund chairs, laboratories, and postgraduate research. All of these specifically aimed at solving local industrial problems, from refinery maintenance to plastic waste conversion.

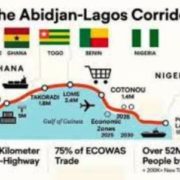

- From Raw Export to Knowledge Export: The goal must be to move up the value chain. The refinery should be the first step towards a full petrochemical industry producing plastics, fertilizers, and pharmaceuticals. This demands a national strategy that prioritizes STEM education, protects intellectual property, and offers tax breaks for R&D. The narrative must change from exporting crude to exporting solutions. These include refined products, chemical expertise, and process engineering services across Africa.

- Political Economy of Dignity: Treating academics as adversaries rather than assets is a profound political failure. Lecturer welfare is not a mere salary issue. It is about creating a dignified knowledge-producing class whose work is valued. A stable, well-resourced academic is a researcher who patents, a teacher who inspires innovation. And a consultant who saves industries millions.

Dangote Refinery is a magnificent accident of capital

In conclusion, the Dangote Refinery is a magnificent accident of capital. But a nation cannot accident its way into sustainable industrial transformation. The difference between an anomalous flash and a forging fire is systemic intentionality. Nigeria stands at a crossroads.It can view the refinery as a destination.Then continue to let its universities the true engines of replication and innovation languish.

Or, it can see it as a starting point, a challenge to build a complementary knowledge infrastructure that would make Nigeria not just the site of Africa’s largest refinery. But the home of Africa’s foremost engineers. The authors of its manufacturing playbook, and the continent’s first genuine producer economy. The choice is between a monument and a movement. The government’s current policy suggests it is content with the monument, while the future, quite literally, strikes on the campuses.