By Dada Hammed Togunde

Abstract

Nigeria’s persistent budgetary failures are commonly attributed to revenue shortfalls, corruption, or weak execution. This article advances a different explanation. It argues that the country’s budget crisis is rooted in the systematic abandonment of the legally mandated budgeting framework introduced through the Economic Reforms and Governance Project and codified in the Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Public Procurement Act of 2007. Central to this framework is the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF), which the law establishes as the binding foundation of the annual budget and the prerequisite for lawful appropriation.

Drawing on constitutional provisions, statutory analysis, and the 2026–2028 MTEF as a case study, the article demonstrates how executive practice, legislative conduct, and institutional failure have collectively eroded the sequencing required by law. It shows that the routine extension of appropriation acts and the insertion of “constituency projects” at the appropriation stage are not merely poor practice but constitute ultra vires and unconstitutional actions that undermine fiscal discipline, fragment capital expenditure, and institutionalise waste.

The article further situates Nigeria’s experience within the broader literature on governance reform failure and isomorphic mimicry, explaining how formal compliance with donor-driven reforms has masked substantive non-implementation. It concludes that restoring budget discipline in Nigeria does not require new laws or frameworks, but strict adherence to existing constitutional and statutory processes, particularly the primacy of the MTEF in budget preparation and approval. Without such adherence, fiscal reform efforts—including recent tax reforms—risk perpetuating inefficiency rather than advancing public welfare.

How Process Failure Became a Constitutional Crisis

Every year, Nigerians are promised hospitals that are never completed, roads that end abruptly, and schools that exist only in budget speeches. Projects appear, disappear, and reappear under new names, while communities wait—year after year—for outcomes that never arrive. For citizens, the national budget has become a document of recurring disappointment rather than a public purpose.

This persistent failure to implement the budget is often blamed on corruption, poor revenue, or weak execution. Those explanations, while convenient and tenable, miss the deeper problem. Nigeria’s budget crisis is not accidental, and it is not merely technical. It is the predictable consequence of abandoning the legally mandated budgeting framework introduced in 2007 and entrenched in the Constitution, the Fiscal Responsibility Act, and the Public Procurement Act.

Nearly two decades after those reforms, Nigeria continues to operate a budgeting system that observes form while violating substance. The result is a process that looks constitutional but functions unlawfully—one that produces plans without discipline and appropriations without foundations.

The Budget Is a Legal Process, Not a Political Season

Under Nigeria’s constitutional framework, budgeting is not a discretionary political ritual. It is a rule-based, sequential legal process.

The Constitution establishes the Consolidated Revenue Fund and restricts withdrawals from it except as authorised by law. The Fiscal Responsibility Act gives operational meaning to this framework by introducing the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF), which section 18(1) of the Act explicitly designates as the legal basis of the annual budget. In other words, the budget as a plan exists before appropriation. Appropriation merely authorises spending; it does not invent priorities. The introduction of MTEF ensures multiperiod budgeting for projects with a multi-year timeline, thereby preventing abandonment.

The law also assigns the National Assembly a clear role at a specific stage. Section 13(2) (b) of the Fiscal Responsibility Act mandates the Minister to hold public consultation and seek the input of the stakeholders, including the National Assembly, during the preparation of the MTEF. That is where fiscal priorities, sectoral ceilings, and project choices are to be debated and agreed. Section 14 (2) of the Act empowers the National Assembly to approve the MTEF. Section 15 of the Act requires the MTEF to be published in the Gazette. Once the MTEF is approved and gazetted, appropriation follows as a constitutional formality, not an opportunity for reinvention.

This sequencing is not optional. It is the backbone of fiscal discipline.

How Nigeria Abandoned Its Own Reforms

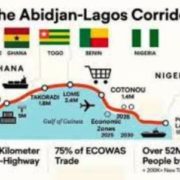

Nigeria’s public financial management reforms emerged from the Economic Reforms and Governance Project (ERGP) initiated in 2004 with World Bank support. The reforms introduced instruments such as the Treasury Single Account, GIFMIS, IPPIS, and IPSAS, alongside the Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Public Procurement Act.

Their purpose was clear: to restore transparency, ensure programme continuity, eliminate abandoned projects, and anchor budgeting in medium-term planning rather than annual improvisation. The problem was not the design of these reforms. It was their abandonment.

Institutions were created, laws enacted, and systems deployed, but implementation was left to agencies lacking the authority, coordination, and capacity to enforce discipline. Over time, the MTEF became a procedural routine rather than the foundation of budgeting. Budget extensions became routine, scrutiny became superficial, and legality became compromised.

For citizens, this translated into projects without timelines, contractors without accountability, and public services without transparency. And the citizens are, in the long run, disappointed.

Institutional Weakness Meets Legislative Overreach

Nigeria’s superfluous budget institutions—the Ministry of Budget and National Planning, the Budget Office of the Federation (with no legal existence), the National Planning Commission, the Fiscal Responsibility Commission, and the Bureau of Public Procurement—now function largely as administrative clearinghouses. Mandates overlap, accountability is diffused, and no institution effectively defends the integrity of the budgeting process.

This institutional weakness has been compounded by legislative overreach. The routine insertion of so-called “constituency projects” at the appropriation stage represents the most visible distortion of the budget framework. These insertions are often defended as a representation and exercise of the power of the purse. In reality, they are unconstitutional.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act confines legislative influence on project selection to the MTEF stage. The MTEF is a consultative exercise. When the National Assembly approves an MTEF without scrutiny, it exhausts that influence. It cannot lawfully recover a right it failed to exercise by introducing projects later at the appropriation stage.

Appropriation is not a marketplace for political bargaining. It exists solely to authorise withdrawals from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for projects already defined in the budget. Any project not embedded in an approved MTEF has no legal standing, no matter how politically attractive it may appear.

The human cost of this practice is severe. Capital budgets are fragmented, scarce resources are spread thin, and projects multiply without the funding or coherence required for completion. Visibility replaces value, and promises replace performance. Projects are not properly costed.

Incessant budget extensions, often driven by the politics of constituency projects, amount to legislative overreach. Section 81(1) of the Constitution requires the President to present estimates of revenue and expenditure for the “next following financial year,” which the Constitution defines under section 318(1) as a twelve-month period beginning on 1 January or as prescribed by the National Assembly. That power was exercised through the Financial Year Act, which fixes Nigeria’s financial year from January to December.

Once the financial year has been prescribed by law, it becomes the temporal boundary of every annual Appropriation Act. An Appropriation Act does not create its own lifespan; it derives its authority entirely from the financial year to which it relates. When that year ends, the authority to spend lapses. Neither a legislative resolution nor an amendment to the Appropriation Act can lawfully extend budgetary authority beyond 31 December without first amending the Financial Year Act. Such extensions persist not because they are lawful, but because they have not been decisively challenged. Arguments based on “continuity of projects” conflate administrative convenience with constitutional power.

Beyond their legal infirmity, budget extensions distort fiscal discipline. Extending annual budgets forces multi-year projects to compete for funding within a single year’s revenue inflow, encouraging excessive borrowing and contributing to project abandonment. This practice persisted until its consequences became evident in 2025, leading to the rollover of unexecuted portions of the 2024 and 2025 budgets into early 2026, without clarity on funding under the 2026 appropriation.

Sound fiscal management requires that annual budgets reflect actual yearly revenues. The Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) provides a constitutionally sound alternative by allowing uncompleted projects to be re-listed and subjected to fresh legislative appropriation in subsequent years, thereby preserving fiscal discipline and restoring annual legislative control.

The 2026 Budget as Evidence of Systemic Breach

The 2026–2028 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework clearly illustrates this systemic failure. Approved with remarkable speed, endorsed by the Federal Executive Council (FEC) on 3 December, 2025, about 6 months late, transmitted to the National Assembly on 10 December,

2025, approved by the Senate on 16 December 2025 and the House of Representatives on 18 December 2025, the MTEF was followed by an Appropriation Bill presented by the President on 19 December 2025 that diverged materially from its parameters.

Aggregate expenditure figures differed, exchange rate assumptions changed, and oil benchmarks varied between legislative chambers. These inconsistencies violate the explicit requirement of section 18(1) of the Fiscal Responsibility Act that the MTEF form the basis of the Appropriation Bill. This is not a technical oversight. It is a legal rupture. In addition, macroeconomic assumptions conflicted with the Central Bank’s projections in its 2026 macroeconomic outlook for Nigeria. This shows a lack of coordination between the fiscal and monetary authorities.

A Contrast in Reform: Lessons from Tax Policy

Recent tax and fiscal policy reforms demonstrate that reform can succeed when authority, competence, and acceptance align. The Presidential Committee on Tax and Fiscal Policy Reform adopted a context-sensitive approach, focused on solving Nigeria’s specific problems rather than on importing generic international best-practice solutions.

The defining success factor of the current tax reform, though, is anticipatory rather than retrospective: it lies in how the reform has been structured to succeed before outcomes are even measured. By constituting an eminent committee of private-sector professionals under the highly competent leadership of Taiwo Oyedele, and deliberately complementing it with a separate implementation committee led by Joseph Tegbe, the President has pre-empted the common failure point of Nigerian reforms—execution drift. This design embeds credibility, delivery discipline, and continuity across both policy formulation and implementation. It stands in sharp contrast to the public financial management reforms under the ERGP, which, despite World Bank–aligned best practices, placed premature load-bearing responsibilities on civil servants and became fragile once reformist technocrats left government. In this sense, the current tax reform’s greatest strength is not yet its results, but the foresight of its institutional architecture to endure beyond personalities and political cycles.

That success, however, will be undermined if the expected increase in revenues continues to flow into a budgeting system that lacks discipline. Tax reform without budget reform merely finances inefficiency. The Taiwo Oyedele committee, whose mandate covers fiscal policy, should conduct a comprehensive review of the budgeting framework and make a well-informed recommendation to the government.

Restoring Budget Discipline and Public Trust

Budgeting is not a seasonal political event; it is a continuous governance function. Nigeria already possesses the legal tools required for discipline. What is missing is fidelity to the sequence prescribed by those laws.

The 2026 budget has already been approved in substance through the MTEF. The role of the Appropriation Act is limited: to authorise withdrawals from the Consolidated Revenue Fund to execute what the law already defines as the budget. Unfortunately, the National Assembly that passed the MTEF without adequate scrutiny will show higher seriousness in the consideration of appropriation, which should be a mere formality. Until Nigeria restores respect for this framework, citizens will continue to live in a country where plans are announced with certainty and outcomes are delivered with apology.

In public finance, legality is not cured by urgency, nor discipline waived by politics. Where the law prescribes a sequence, obedience is not optional.

Dada Hammed Togunde is a seasoned finance and governance professional with an MBA and professional certifications (FCA, ACTI). He has extensive experience in public sector finance, budgeting, audit, and donor-funded programmes. His work focuses on strengthening public financial management, compliance, and institutional reform through policy and advisory engagements.