By Anagba, Joseph Obidi

Africa today is holding more elections than at any time in its history. Constitutions exist. Parliaments sit. Political parties campaign openly. On paper, democracy has spread across the continent.

But a deeper question confronts African societies: is democracy working in practice?

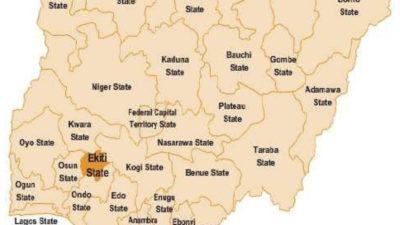

Three decades after the democratic wave of the 1990s, many African countries are discovering that elections alone cannot guarantee stability, prosperity, or public trust. Across the continent, citizens are increasingly frustrated by corruption, unemployment, political instability, and weak institutions. In the Sahel, military coups have returned in places like Burkina-Faso, Mali, and Niger Republic. In others, democratic systems exist but struggle to deliver meaningful change and reforms.

This is not a rejection of democracy. It is a demand for a better one.

The Promise and the Disappointment

Africa’s democratic journey began with enormous hope. South Africa’s 1994 transition from apartheid showed the world what inclusive democracy could achieve. Nigeria’s return to civilian rule in 1999 ended decades of military dominance and raised expectations of accountable governance. Ghana steadily built a reputation for peaceful transfers of power.

Yet progress has been uneven. Kenya’s 2007 election crisis, which descended into violence, exposed how fragile democratic institutions can be when electoral credibility collapses. Zimbabwe’s prolonged political crisis under Robert Mugabe demonstrated how leadership without accountability can hollow out democratic structures. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, repeated electoral controversies and armed conflict have made stable governance elusive.

These cases show a consistent pattern: when citizens lose confidence in elections, democracy loses its moral authority.

Corruption and the Erosion of Trust

One of the greatest threats to democracy in Africa is corruption. It is not simply a financial crime it is a political disease that weakens institutions and destroys public confidence.

Nigeria’s long history of corruption scandals, including controversies in the oil sector, has repeatedly shaken trust in governance. South Africa’s “state capture” saga during the Jacob Zuma era revealed how political power can be manipulated for private gain. Kenya’s National Youth Service scandal showed how corruption can infiltrate even programs meant to empower young people.

When citizens believe that leaders enrich themselves while the public suffers, democracy begins to look like a façade.

Democracy and the Economy

Economic realities shape political stability. Democracy cannot survive on ballots alone it must deliver jobs and opportunity.

Countries that invest in industrial growth often experience greater political resilience. Before its internal conflict, Ethiopia’s industrial park strategy created thousands of manufacturing jobs and strengthened public optimism about reform. Ghana’s Government initiatives such as One District, One Factory (1D1F) were designed to decentralise industrial activity, promote regional equity, and generate employment beyond Accra. Such efforts to expand agro-processing and small industries have helped spread economic opportunity beyond major cities. Senegal’s gradual industrial development has provided an economic cushion that supports political stability.

On the other hand, Tunisia’s experience after the 2011 revolution shows the danger of economic stagnation. Rising unemployment and declining industrial competitiveness weakened faith in democratic institutions and contributed to political regression.

For millions of Africans, democracy is meaningful only when it improves daily life.

Poverty and Participation

Poverty limits political participation. When citizens struggle for survival, civic engagement becomes secondary. Democracy requires informed and active citizens, yet extreme inequality prevents many from accessing education, information, and political space.

Botswana’s relative economic success has reinforced its stable democratic system. By contrast, countries facing prolonged poverty and conflict, such as Somalia and parts of the DRC, find it difficult to sustain democratic governance.

The lesson is simple: democracy and development must move together.

Ethnicity, Identity, and Power

Ethnic politics remains a powerful force in many African democracies. In multi-ethnic states such as Nigeria and Kenya, elections often follow identity lines. Political competition becomes a struggle for access to state resources rather than a contest of ideas.

This dynamic deepens division and weakens national cohesion. When power is seen as belonging to one group at the expense of others, democracy becomes a zero-sum game.

Inclusive leadership is essential. Democracies that manage diversity fairly are more likely to survive political shocks.

A New Battlefield: Digital Democracy

The fight for democracy has entered the digital age. Social media has energized youth movements and expanded political participation across Africa. Nigeria’s #EndSARS protests demonstrated how digital platforms can mobilize citizens rapidly. These developments underscore the growing role of young, digitally connected populations in shaping political discourse and challenging entrenched power structures.

Yet governments increasingly respond with internet shutdowns and digital surveillance during elections and protests. In Tanzania, for instance, authorities imposed a near-nationwide internet blackout during the 2025 general election amid allegations of electoral manipulation and violent suppression of protests. This struggle over digital space reflects a larger tension between citizen empowerment and state control.

The Way Forward

Africa does not lack elections. It lacks strong institutions.

Independent electoral commissions, impartial courts, professional security services, and credible anti-corruption agencies are the true guardians of democracy. Civic education must teach citizens not only how to vote, but how to hold leaders accountable. Regional organizations must consistently defend constitutional rule instead of tolerating military takeovers.

The continent’s future depends on transforming democratic form into democratic substance.

Africa’s democratic story is not one of failure. It is one of unfinished work. Countries such as Ghana, Botswana, Senegal and Cabo Verde show that progress is possible. Others provide cautionary lessons about the cost of institutional decay.

Africans are not turning away from democracy. They are demanding a system that delivers fairness, opportunity, and dignity.

Elections open the door. Institutions keep democracy alive.

Anagba, Joseph Obidi, Research Fellow, Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR), Abuja, Nigeria.